Method of matched asymptotic expansions

In mathematics, particularly in solving singularly perturbed differential equations, the method of matched asymptotic expansions is a common approach to finding an accurate approximation to a problem's solution.

Contents |

Method overview

In a large class of singularly perturbed problems, the domain may be divided into two subdomains. On one of these, the solution is accurately approximated by an asymptotic series found by treating the problem as a regular perturbation. The other subdomain consists of one or more small areas in which that approximation is inaccurate, generally because the perturbation terms in the problem are not negligible there. These areas are referred to as transition layers, or boundary or interior layers depending on whether they occur at the domain boundary (as is the usual case in applications) or inside the domain.

An approximation in the form of an asymptotic series is obtained in the transition layer(s) by treating that part of the domain as a separate perturbation problem. This approximation is called the "inner solution," and the other is the "outer solution," named for their relationship to the transition layer(s). The outer and inner solutions are then combined through a process called "matching" in such a way that an approximate solution for the whole domain is obtained.[1][2][3]

Simple example

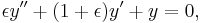

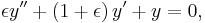

Consider the equation

where  is a function of

is a function of  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.

Outer and inner solutions

Since  is very small, our first approach is to find the solution to the problem

is very small, our first approach is to find the solution to the problem

which is

for some constant  . Applying the boundary condition

. Applying the boundary condition  , we would have

, we would have  ; applying the boundary condition

; applying the boundary condition  , we would have

, we would have  . At least one of the boundary conditions cannot be satisfied. From this we infer that there must be a boundary layer at one of the endpoints of the domain.

. At least one of the boundary conditions cannot be satisfied. From this we infer that there must be a boundary layer at one of the endpoints of the domain.

Suppose the boundary layer is at  . If we make the rescaling

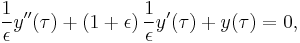

. If we make the rescaling  , the problem becomes

, the problem becomes

which, after multiplying by  and taking

and taking  , is

, is

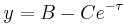

with solution

for some constants  and

and  . Since

. Since  , we have

, we have  , so the inner solution is

, so the inner solution is

Matching

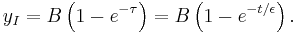

Remember that we have assumed the outer solution to be

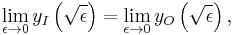

The idea of matching is for the inner and outer solutions to agree at some value of  near the boundary layer as

near the boundary layer as  decreases. For example, if we fix

decreases. For example, if we fix  , we have the matching condition

, we have the matching condition

so  . Note that instead of

. Note that instead of  , we could have chosen any other power law

, we could have chosen any other power law  with

with  . To obtain our final, matched solution, valid on the whole domain, one popular method is the uniform method. In this method, we add the inner and outer approximations and subtract their overlapping value,

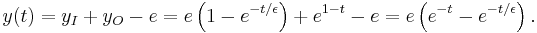

. To obtain our final, matched solution, valid on the whole domain, one popular method is the uniform method. In this method, we add the inner and outer approximations and subtract their overlapping value,  . In the boundary layer, we expect the outer solution to be approximate to the overlap,

. In the boundary layer, we expect the outer solution to be approximate to the overlap,  . Far from the boundary layer, the inner solution should approximate it,

. Far from the boundary layer, the inner solution should approximate it,  . Hence, we want to eliminate this value from the final solution. In our example,

. Hence, we want to eliminate this value from the final solution. In our example,  . Therefore, the final solution is,

. Therefore, the final solution is,

Accuracy

Substituting the matched solution in the problem's differential equation yields

which implies, due to the uniqueness of the solution, that the matched asymptotic solution is identical to the exact solution up to a constant multiple, as it satisfies the original differential equation. This is not necessarily always the case, any remaining terms should go to zero uniformly as  . As to the boundary conditions,

. As to the boundary conditions,  and

and  , which quickly converges to the value given in the problem.

, which quickly converges to the value given in the problem.

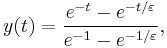

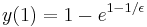

Not only does our solution approximately solve the problem at hand; it closely approximates the problem's exact solution. It happens that this particular problem is easily found to have exact solution

which, as previously noted, has the same form as the approximate solution bar the multiplying constant. Note also that the approximate solution is the first term in a binomial expansion of the exact solution in powers of  .

.

Location of boundary layer

Conveniently, we can see that the boundary layer, where  and

and  are large, is near

are large, is near  , as we supposed earlier. If we had supposed it to be at the other endpoint and proceeded by making the rescaling

, as we supposed earlier. If we had supposed it to be at the other endpoint and proceeded by making the rescaling  , we would have found it impossible to satisfy the resulting matching condition. For many problems, this kind of trial and error is the only way to determine the true location of the boundary layer.[1]

, we would have found it impossible to satisfy the resulting matching condition. For many problems, this kind of trial and error is the only way to determine the true location of the boundary layer.[1]

See also

References

- ^ a b Verhulst, F. (2005). Methods and Applications of Singular Perturbations: Boundary Layers and Multiple Timescale Dynamics. Springer. ISBN 0-387-22966-3.

- ^ Nayfeh, A. H. (2000). Perturbation Methods. Wiley Classics Library. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-39917-9.

- ^ Kevorkian, J.; Cole, J. D. (1996). Multiple scale and singular perturbation methods. Springer. ISBN 0-387-94202-5.